Fear of humans exceeds that of lions throughout a variety of mammal species in a South African national park, research published in Current Biology finds.

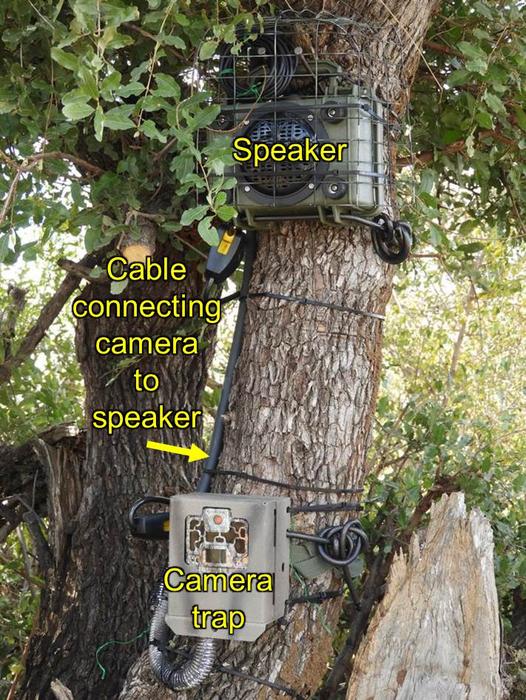

South Africa’s Greater Kruger National Park is one of Africa’s premier protected areas and possesses one of the world’s largest remaining lion populations. In 2022, a waterhole in its center provided the stage for a long-term behavioral study. Researchers led by conservation biologist Liana Zanette (University of Western Ontario) tested the reaction of 19 mammal species on a variety of sounds. Using an automated camera-speaker system, the team exposed animals to playbacks of talking humans, hunting sounds (dogs and gunshots), lions and a control sound (birds).

Video recordings indicate that fear of humans significantly exceeds that of other sounds. On average, the mammals were “twice as likely to run and abandoned waterholes in 40% faster time in response to humans than to lions or hunting sounds”. A total 95 percent of the tested species – elephants, rhinos and giraffes, among others – showed greater fear of humans, compared to both lions and barking dogs or gunshots. Put another way: It seems not to be specific hunting sounds that trigger the greatest fear – it’s the presence of homo sapiens itself.

Some spectacular videos of mammal reactions on human vocalizations can be seen HERE.

“I think the pervasiveness of the fear throughout the savannah mammal community is a real testament to the environmental impact that humans have,” states first author Zanette. “Not just through habitat loss and climate change and species extinction, which is all important stuff. But just having us out there on that landscape is enough of a danger signal that they respond really strongly. They are scared to death of humans, way more than any other predator.”

The conclusion that fear itself has ecosystem-level impacts by reducing growth rates (as fleeing often goes along with the expense of eating and staying in good condition), modifying movements and modifying day-night-rhythms builds on research from the last 200 years. Already Darwin discussed fear of humans in wild animals in his famous The Voyage of the Beagle. What is new, Zanette concludes, is “the comprehension of the great degree and pervasiveness of this fear”. Research from different parts of the world has shown that mountain lions, deer, kangaroos, wallabies and wild boar also fear humans more than other predators.

“The fear of humans is ingrained and pervasive, so this is something that we need to start thinking about seriously for conservation purposes”, says co-author Michael Clinchy, also a conservation biologist at University of Western Ontario.

The implications include challenges for wildlife tourism. African protected areas like Kruger National Park in South Africa largely rely on funding by wildlife tourism and therefore frequent human-wildlife interaction. Reducing wildlife exposure as a result of Zanette’s study would therefore question the economic sustainability of national parks. But at the same time, it may be an ecologically crucial building block of conservation.

The whole study was published in Current Biology.